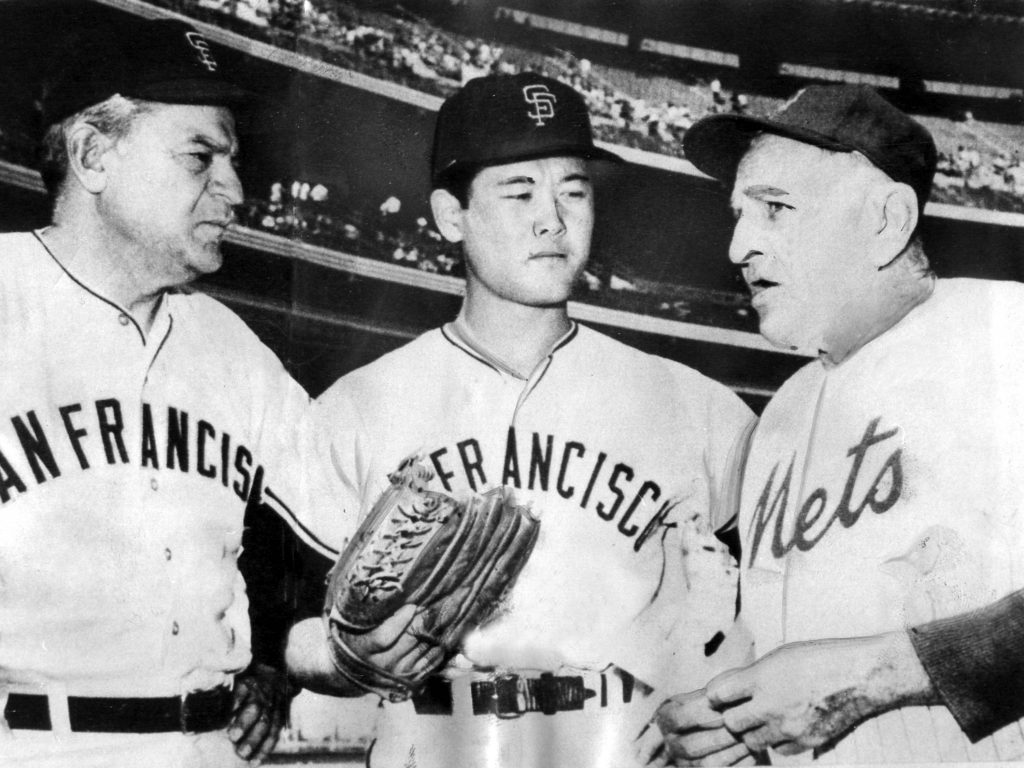

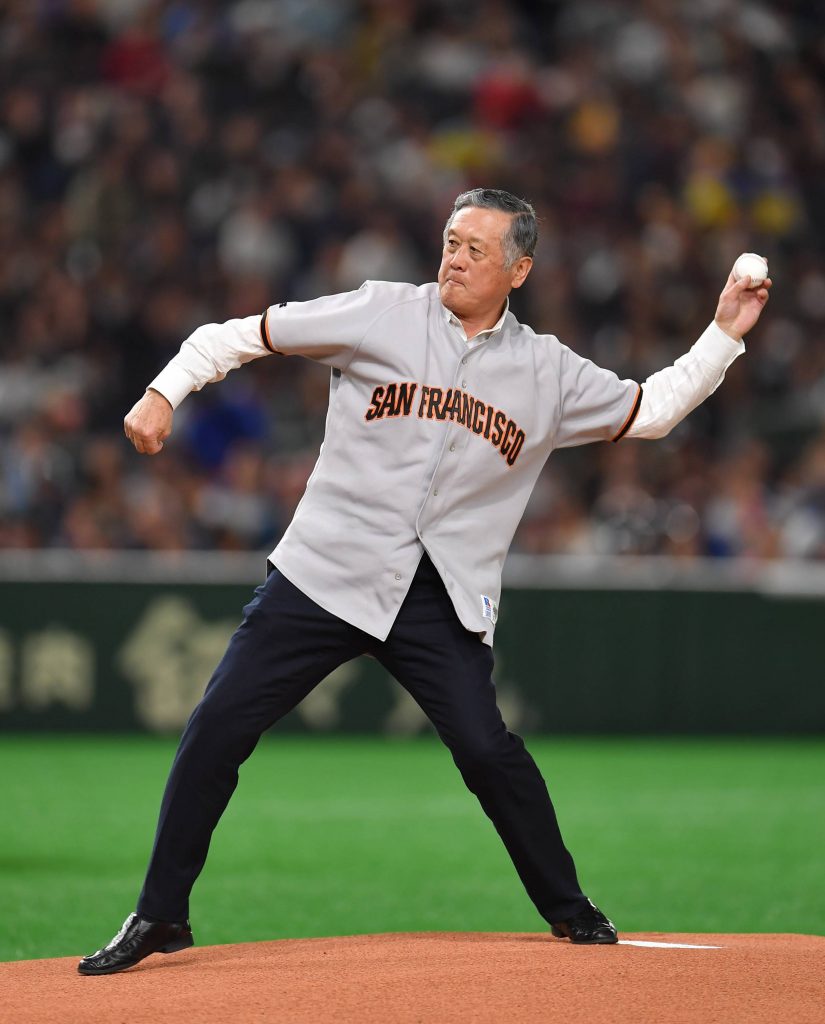

Masanori Murakami speaks before the San Francisco Giants-Los Angeles Dodgers game on "Masanori Murakami Night" at Candlestick Park in San Francisco on August 5, 1995.

Every once in a while, like a lot of people, I come up with a good idea.

Rarely does this idea proceed out of my brain and onto paper.

However, nearly 30 years ago one did and it resulted in something very positive.

Turn back the clock to 1993, and I had just finished working two years as the Director of Public Relations for the London Monarchs of what was then known as the World League of American Football. It later became the NFL Europe.

I was in between gigs as we say in the business, and looking for my next project. It also so happened that at the time my girlfriend (later my wife) was Japanese.

At this point in my life, I knew almost nothing about Japan except for Sony TVs and Nissan automobiles. That was it.

One day I was walking through the shopping mall in my hometown of San Jose, California, and in the window of a bookstore something caught my eye. It was a copy of Robert Whiting’s You Gotta Have Wa that featured a very creative cover. Hoping to learn more about Japan, I purchased the book.

I figured the easiest way for me to learn about Japanese culture at the outset may be through the window of sports. So I read this book with great interest and eventually moved on to many other non-sports tomes in an effort to obtain as much information as I could about Japan.

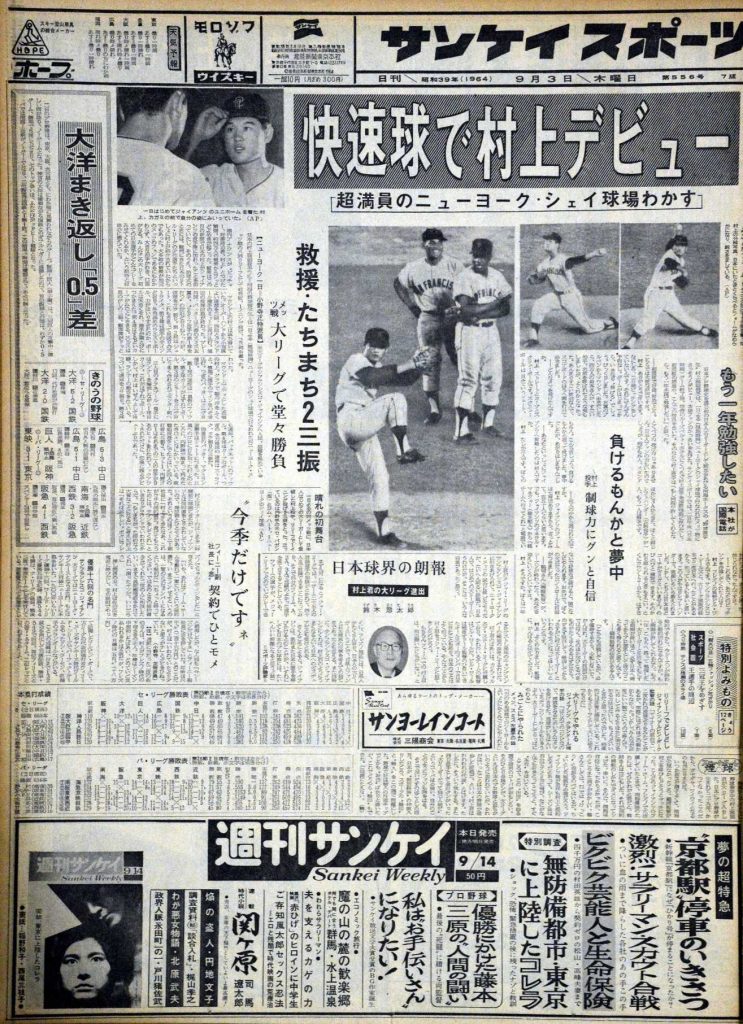

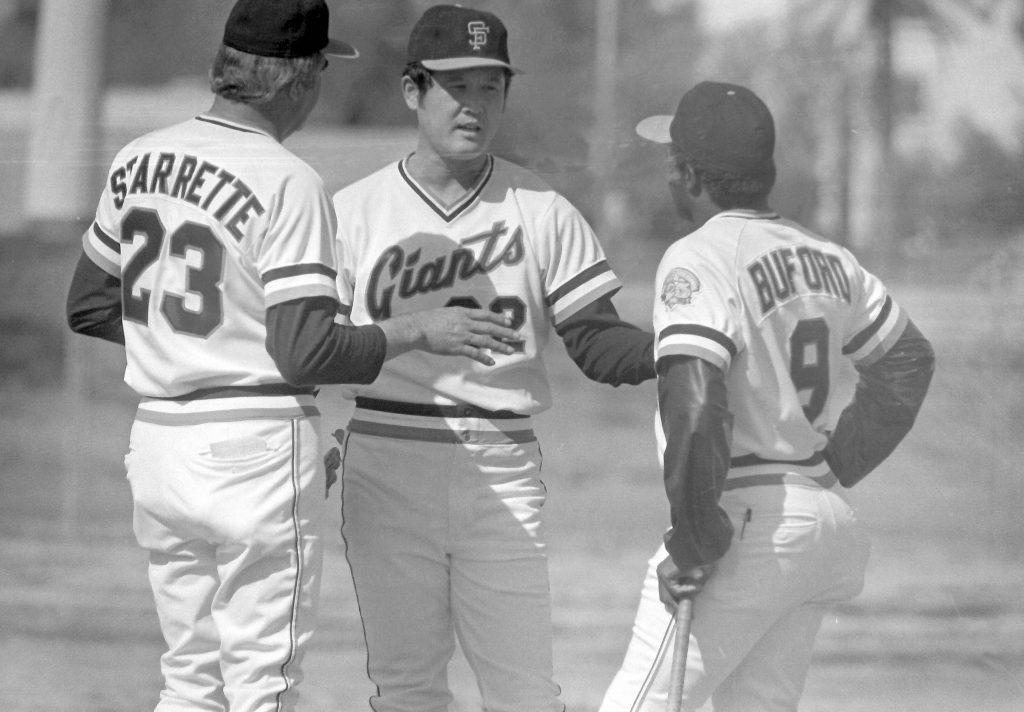

Murakami’s Debut Season in MLB

While reading You Gotta Have Wa, I first learned of the story of Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, the first Japanese to play Major League Baseball. He was a relief pitcher for my beloved San Francisco Giants in 1964-65.

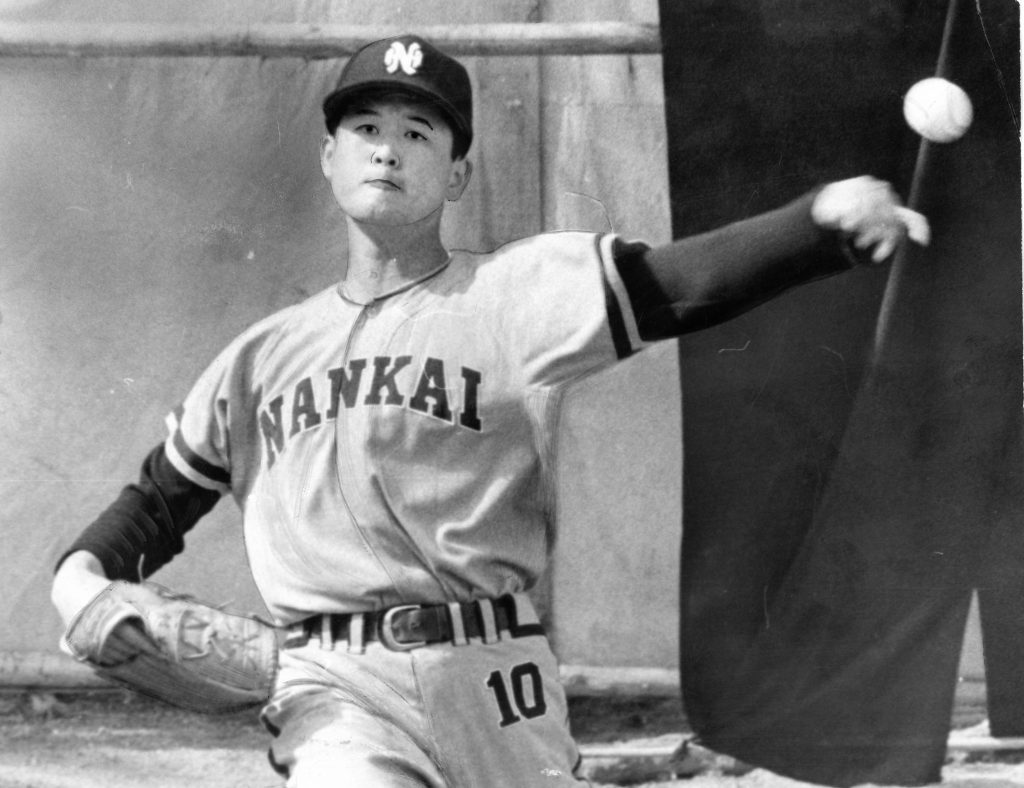

Being just a few years old at the time, I had no memory of this, but was intrigued by what I read. Murakami had originally come to the United States along with two teammates (catcher Hiroshi Takahashi and infielder Tatsuhiko Tanaka) from the Nankai Hawks in the spring of 1964 as kind of a working agreement with the Giants.

Murakami was just 19 when he left Japan for the US and was promptly sent to the Fresno Giants of the Class-A California League along with his teammates. Murakami proceeded to tear up the circuit and was named the Rookie of the Year with an 11-7 record and a 1.78 ERA as the Giants won the pennant.

A native of Otsuki, Yamanashi Prefecture, Murakami was called up to the major league team on September 1, 1964, and made his debut at New York’s Shea Stadium against the Mets that night. He joined a Giants squad that featured five future Hall of Famers in Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal, Gaylord Perry and Warren Spahn.

“History was made when Japan and the United States joined hands and played the game that both countries claim as their national pastime,” read an account in one Bay Area newspaper following Murakami’s debut.

Murakami did well in the majors that season, going 11 innings before allowing an earned run. The Giants were thrilled with this new gem they had found.

Labor Dispute Between Giants, Hawks

In the contract the Giants had signed with the Hawks was a clause stating that for $10,000 the Giants could buy the rights to any of the three Japanese players. The Hawks didn’t think this was a concern as the young players going to the States would be playing in the minors.

A dispute ensued after the 1964 season and at one point baseball relations between the US and Japan were severed by MLB commissioner Ford Frick. The row was eventually resolved with the proviso that Murakami would pitch for the Giants in 1965, then return to Japan in 1966. The hullabaloo caused Murakami to miss all of training camp and the first three weeks of the 1965 season.

His final MLB numbers were a 5-1 record, with a 3.43 ERA and nine saves in 54 career games.

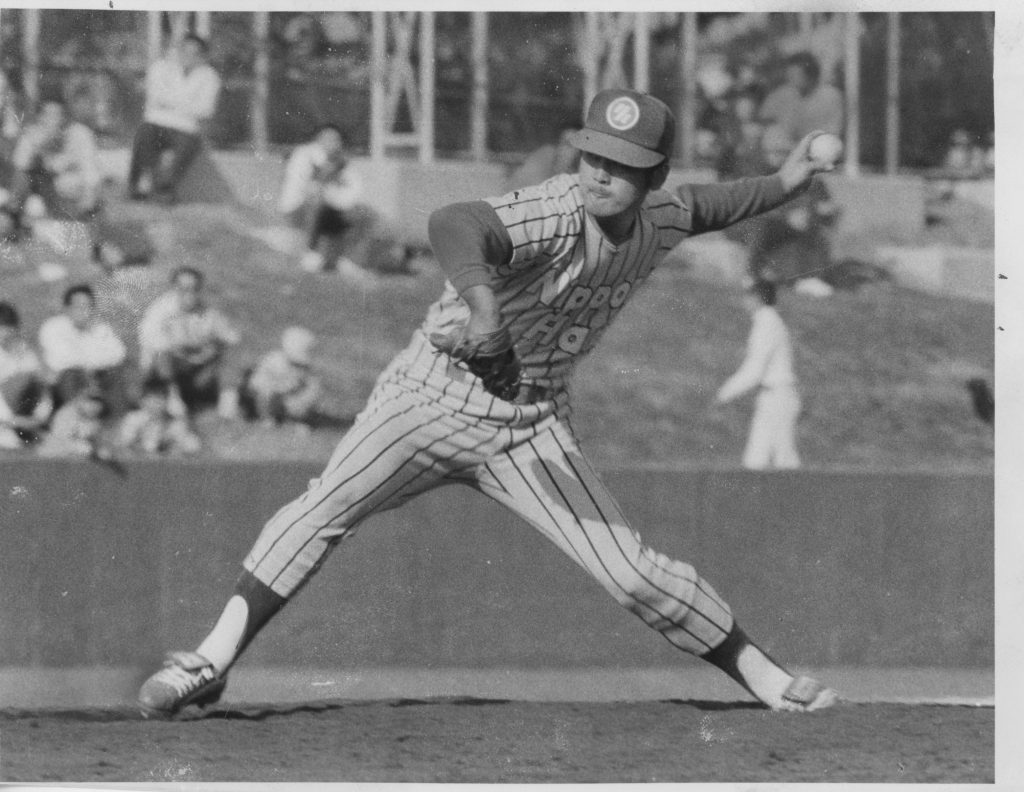

Murakami went on to have a solid career in Japan, going 103-82 with a 3.64 ERA for the Hawks, Hanshin Tigers and Nippon Ham Fighters, before retiring in 1982.

At the age of 38 in 1983, Murakami attempted to return to the Giants via a training camp invite. He pitched well in exhibition games, but was manager Frank Robinson’s final cut that spring.

At that point, Murakami lost contact with the Giants for some 10 years as the management of the team repeatedly turned over. He returned to Japan and went on to become a pitching coach in NPB.

The Origin of a Big Idea

After reading about Murakami’s story, the light bulb went on in my head and I said, “This guy is a real pioneer, we have to recognize him for what he accomplished and bring greater awareness to his incredible achievement.”

In the summer of 1993, I made my first trip to Japan. It was overwhelming to say the least. Never imagining I would come here, I found myself traveling around the country on the Shinkansen and visiting places like Hiroshima and Fukushima. It was mind-blowing.

One of the goals I set out before the trip was to find Murakami and hear his story firsthand. My girlfriend called the office of the Seibu Lions, where Murakami was coaching the club’s minor league team. He called back and agreed to meet with us.

I thought we might get 15 minutes with him. He instead spoke to us for three hours about his fond memories of time in the US and the major leagues. It was fascinating. I felt like I had found the Holy Grail.

“I wish I could have stayed in America for a few more seasons to see what I could have done over a longer period of time,” Murakami said to me. “But I attribute my success in baseball to my experience in the States. It was such a great thrill, and people were so kind to me. Everyone should be as lucky as I am.”

At the end of the meeting, I explained to Murakami that I was drafting up a plan to bring him to San Francisco for a series of events in his honor. There was no guarantee, I said, but I thought I could pull it off.

It so happened that the recently hired Vice President of Public Relations for the Giants at the time was Bob Rose, who had been the Vice President of Communications for the World League when I was a part of it. Bob and I had a good working relationship from our days in football.

I proceeded to write up a proposal for a three-pronged tribute to Murakami. There would be a reception, a youth baseball clinic in San Francisco’s Japantown, and a night at the ballpark in his honor.

A Meeting with Giants Management

Rose had me meet with the management of the Giants at Candlestick Park in early 1994 and they liked my idea, but there was initially some resistance from one of the senior bean counters.

“That is going to cost $10,000!” the person said, I was informed.

When I heard that, I remember thinking, “Can’t this guy see that this project is going to be a huge hit with the Japanese-American community in the Bay Area and Northern California?”

It was ultimately agreed that there would be a “Masanori Murakami Night” in August of 1994 against the Pittsburgh Pirates to celebrate the 30th anniversary of his debut in the majors.

Then fate intervened when the players went on strike on August 12, 1994, a week before the events for Murakami were to be held. The Giants canceled the festivities and MLB entered a cold war that endured until the following April.

Major Life Changes for the Author

By the time the MLB players finally retook the field on April 25, 1995, my life had undergone a tectonic change. I was now living in Japan and working as a sports writer at The Daily Yomiuri, the English newspaper of The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Also, that offseason Hideo Nomo had retired from the Kintetsu Buffaloes and NPB and joined the Los Angeles Dodgers. Nomo would later come to play a role in the unfolding saga of Murakami’s night with the Giants.

Once matters settled down, the Giants contacted me and reiterated their wish to honor Murakami. By now he had left the field and was a broadcaster for NHK on MLB games. He was delighted when I gave him the news.

He made one request: “Tell them I would like the game to be against the Dodgers.”

I relayed the request to Rose and the decision was made to hold the night for Murakami on August 5, 1995, against the Dodgers at Candlestick Park. It was still a long way off, but I hoped to be there as I continued to coordinate with the Giants and Murakami from Japan.

(Pat Sullivan/AP)

Nomo Excels as an MLB Rookie

Nomo proceeded to make a splash for the Dodgers on the way to starting the All-Star Game and winning the National League Rookie of the Year award. I could see the confluence of events coming into focus now.

At this point all of the teams in MLB were still struggling to regain fans who were outraged by the players’ strike and subsequent cancellation of the World Series the season before.

I looked at the schedule of the Dodgers and Giants and contacted Rose again. “Get the Dodgers to change their pitching rotation so Nomo starts on Murakami’s night,” I told him.

Giants owner Peter Magowan contacted Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley and made the request. When the Dodgers came out of the All-Star break, their pitching rotation had been altered and Nomo was slotted in to pitch on August 5 against the Giants.

You can imagine that at this point, I was full of excitement and expectations, hoping to see this dream I had envisioned become a reality.

There was just one problem. The individual I was working for at the newspaper didn’t see fit to give me the time off that I needed to go and see my project come to life.

It was obvious to me that I had to make a choice: go to attend the events for Murakami and lose my job, or stay and watch from thousands of miles away as the idea I created came to fruition.

Having been in Japan for less than a year, I chose the latter. It was a difficult decision to accept and one I have often reflected on over the years.

RELATED:

- From 2020, Ed Odeven’s eight-part Nomomania series.

Fond Memories of a Baseball Trailblazer

One of the amazing things that happened on this journey was the people I talked to who gave their remembrances of Murakami’s time with the Giants. People he played with and against, his manager in Fresno, Bill Werle, and Art Santo Domingo, the Giants PR man back then.

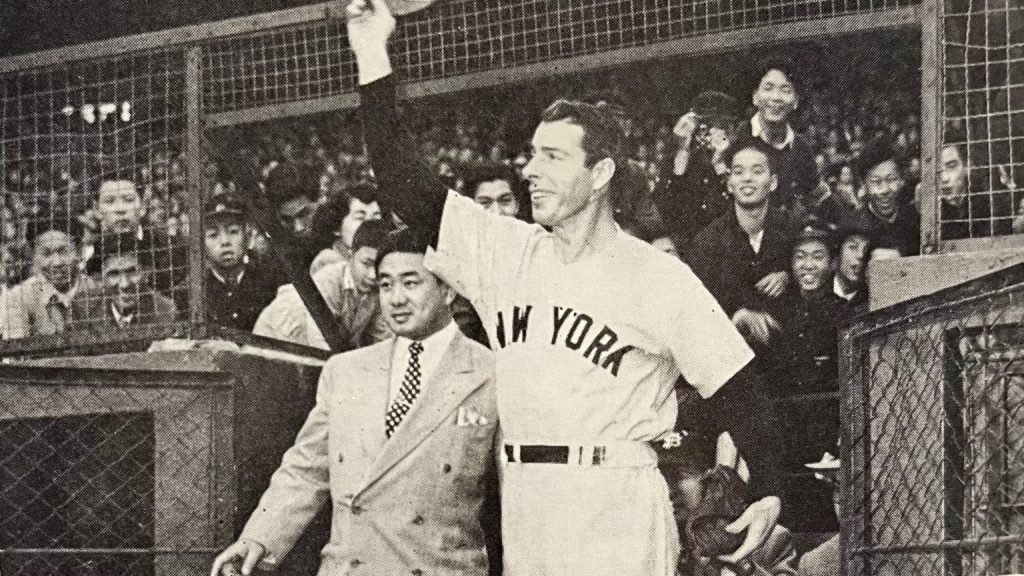

Of all those I spoke with, one stood out ― Cappy Harada, a nisei who worked for the Giants and helped facilitate the Hawks sending the three players to the United States. Harada was wounded twice fighting for the US in World War II. After the war ended, Harada worked for Gen. Douglas MacArthur at the GHQ in Tokyo. MacArthur put him in charge of restarting sports in Japan. Harada may have achieved his greatest exposure in 1954, when he played host to Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe during their honeymoon in Japan.

The events for Murakami came off perfectly, with stories about his return leading the evening news on several Bay Area TV stations that week. After the clinic in Japantown, the Giants had an overflow turnout at the reception for Murakami.

A person who attended told me, “They sold all of the tickets they had on hand and then just let everybody else who came in for free.” I was informed that there were hundreds of people there.

The Giants had invited Murakami and his family to San Francisco for the celebration. They were introduced on the field before the game where Murakami spoke in English and thanked the Giants for recognizing him. I wrote the speech he gave that night and faxed it to him at his hotel beforehand.

Murakami’s Gratitude on Display

Because I was unable to attend, I sent my mother in my place. Murakami made a special point of thanking her in his private box before the game.

The Giants’ largest crowd of the season to that point (43,167) turned out to watch Murakami be honored and Nomo pitch. Nomo proceeded to toss a fantastic one-hit, complete game the Dodgers won 3-0 before a national TV audience. Nomo had two hits of his own in the victory that night.

Sometime later, after Murakami had returned to Japan, he invited me over to his house to view a tape of all the events. I wept as I watched them.

The Giants invited Murakami to be a guest coach at spring training in 1995 and also 1996, when they hired him as a scout for Japan. Murakami paid for my wife and I to join him in Arizona for several days in the spring of 1996.

Murakami, now 78, has maintained a good relationship with the Giants through the years, returning for subsequent celebrations on the 40th and 50th anniversaries of his historic debut and even having a Bobblehead Doll issued in his honor.

He has been invited to the Giants’ annual fantasy baseball camp several times, with longtime Giants announcer Duane Kuiper observing: “He is always the most popular guy there.”

Author: Jack Gallagher

The author is a veteran sports journalist and one of the world’s foremost figure skating experts.