Culture

The British in Bakumatsu Japan: The Tozenji Incident

This is the first installment in a series on the turbulent era of Bakumatsu Japan and encounters between the British legation and samurai of the Meiji era.

Published

4 years agoon

By

Paul Martin

(First of 5 parts in a series on Bakumatsu Japan.)

Part 2: The British in Bakumatsu Japan: The Namamugi Incident

Part 3: The British in Bakumatsu Japan: The Anglo-Satsuma War

Part 4: The British in Bakumatsu Japan: The Bizen Incident

The Bakumatsu era and subsequent Meiji restoration was a turbulent time in Japan. It was a bittersweet, complicated period in Japanese history — filled with feats of great valor mixed with the sadness of needless ritual suicides and assassinations of passionate young men of opposing forces who all, at the end of the day, only want the same thing: to protect the country that they loved.

There are various storylines that interlink and overlap the many different complicated aspects of this period. This series of articles focuses on events involving British civilians and legation or embassy staff in Japan during the turbulent Bakumatsu era. It features images and eye-witness accounts and reports from the time.

The articles are published in chronological order.

Today, in the sleepy back streets of Takanawa — a Minato ward suburb of Tokyo close to Shinagawa, and about a 15-minute walk away from the graves of the 47 Ronin at Sengakuji — is a sedate little Buddhist temple called Tozenji (東禅寺).

Tozenji is part of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism that has its headquarters at the Myoshin-ji temple in Kyoto. Originally founded in Akasaka in 1609 by the Zen monk, Reinan Suroku, it was moved to its current location in 1636 when Tokyo was known as Edo. The temple is where the first British legation to Japan set up a residence in 1859.

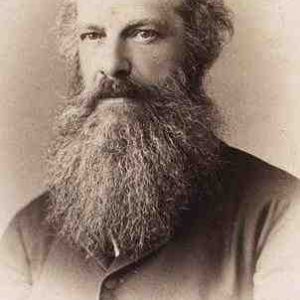

The head of the legation between 1858 and 1864 was Sir Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897). Alcock had previously served as consul at the port of Fuchow in China. He came to Japan in 1858 and eventually set up a British legation in the grounds of Tozenji. However, at that time, Japan was experiencing domestic unrest following over 200 years of Tokugawa shogunate rule, isolation policy, the subsequent rather forceful opening of its doors to the West by the black ships of Commodore Matthew Perry, and onslaught of other foreign countries coming to Japan with their unfair treaties. To many samurai, the appearance of arrogant foreigners on their land was unbearable, particularly to the rather extremist group known as Sonno Joi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians).

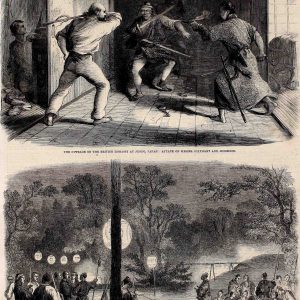

In objection to the legation, the temple was attacked twice — actually three times, if you include the murder of Alcock’s native Japanese translator at the temple gates in early 1860. The main attack occurred during the night of July 5, 1861.

Along with Alcock, other British diplomatic members on the grounds that evening included the First Secretary, Laurence Oliphant (1829-1888). Oliphant had only been in Japan a month and had arrived at the legation a few days prior, while Alcock had been away on business with the British Consul for Nagasaki, George S. Morrison (1830-1893). Morrison had returned to Edo together with Alcock, and was also staying at the legation. Another member involved in the incident was John Frederick Lowder (1843-1902). Lowder had joined the legation the year before as a translator.

Just before midnight, on the evening of July 5, a band said to be of masterless warriors, commonly known as ronin, tried to gain access to the temple grounds via a side gate. The gatekeeper, alerted by the noise, was killed when confronting them. They also killed a dog on the path to the courtyard, as well as an unfortunate horse keeper who happened to cross their path.

One group continued into the building through the kitchen where they came across the cook. They tried to interrogate him as to the whereabouts of members of the legation, and when he refused, they slashed him as well. Luckily, he survived the attack.

They came across another guard. They grabbed him, and threatened him with his life to try to get information about the location of the foreigners. He feigned complicity, but was slashed across his body while trying to escape to raise the alarm. He managed to survive to tell the tale by hiding in the temple pond.

The assailants then broke into three smaller groups and tried to gain entry to the living quarters at four or five different points. The ensuing noise alerted everyone in the quarters.

In order to better convey the terror and confusion of the incident, the following account is in the words of the prime witness himself, Sir Rutherford Alcock, recorded in his memoirs, The Capital of the Tycoon: A Narrative of Three Years in Japan (Vol. II) (Harper & Brothers New York, 1863). I have adjusted some of the text and words from the original into contemporary commonly used words and spellings.

July 5, 1861

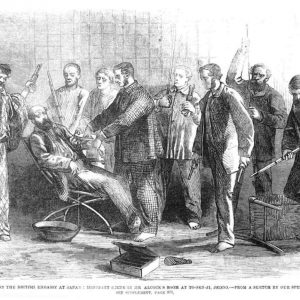

[One of the young student interpreters] stood by my bedside with his dark lantern and awoke me with the report that the legation was attacked and men were breaking in the gate. I got up, incredulous, believing it was some gambling or drunken quarrel either among the guards or the monks in charge of the stables; but after taking a revolver out of its case, I was proceeding to the spot, and had hardly advanced five steps towards the entrance when Mr. Oliphant suddenly appeared covered with blood, which was streaming from a great gash in his arm and a wound in his neck. And the next instant, Mr. Morrison, the Consul of Nagasaki, appeared also, exclaiming he was wounded, and with blood flowing from a sword-cut on his forehead. I, of course, looked for the rush of their assailants pursuing — and I stood for a second ready to fire, and check their advance, while the wounded passed on to my bedroom behind. I was the only one armed at this moment, for, although Mr. Morrison still had three barrels, he was blinded and stunned with his wound.

To my astonishment, no pursuers followed. One of our party (now grouped around me) broke open my other pistol-case and armed himself, but two others had no sort of weapon. Mr. Oliphant had encountered his assailants in the passage leading from his room with only a heavy hunting-whip hastily snatched from his table on the first alarm. We had in fact been taken by surprise — the guards first and ourselves later, and no sign of anyone coming to our rescue appeared — of all the hundred and fifty surrounding the house.

Mr. Oliphant was bleeding so profusely that I had to lay down my pistol and bind up the wound in his arm with my handkerchief; and while so engaged, there was a sudden crash and the noise of a succession of blows in the adjoining apartment. Some of the band were evidently breaking through the glazed doors opening into the court with a frightful fracas; still no [samurai] officials or guards seemed attracted by the noise!

A double barrel rifle had by this time been loaded; but still there were five Europeans only, including a servant — imperfectly armed, and with two more disabled, whom we were afraid to leave for an instant exposed to the fury of a band of assassins of whose number we could form no guess — neither could we tell from what quarter they might be upon us. Whether many or few, they were left in the entire possession of the house for a full ten minutes. It may well be conceived that suspense and anxiety made the time seem still longer.

While they were engaged breaking their way into the room, or out of it — for this we could not tell, and uncertain at what moment they might either come pouring through some windows close to the ground within a yard of the point they were breaking down; I had a moment’s hesitation, whether from the window immediately facing we should not shoot a volley into them at point blank range? But we were so few, and they might be numerous enough to rush in and overpower any resistance. On the other hand, they evidently had missed their way to my apartments — and every minute lost to them was a priceless gain to us since it could not be, that the guard to whom our lives were entrusted would abandon us altogether, unless there was treachery. The unwillingness to leave Mr. Oliphant lying helpless on the floor — even for a short space, in the terrible uncertainty as to what point an attack might come from, turned the balance and determined me to stand, and wait for the issue.

The noise subsided; there was reason to hope rescue had come, or at least a diversion from without, and that the assailants had turned in some other direction, or perhaps made their retreat. Then only I ventured with two of the party to leave the wounded, and go look for one of our number at a farther wing of the building who had never appeared, and might have been less fortunate. While advancing I put one of the students, Mr. Lowder, as a sentry at an angle commanding a long passage leading from the entrance, and the approach from two other directions—and had scarcely advanced ten steps, when a shot from his pistol suddenly recalled me. A group of armed men had appeared at the farther end, and, not answering his challenge, he had very properly fired into them, and as it was down a passage, he could scarcely have missed his aim — at all events they suddenly retreated. And this was the last we saw of our assailants!

Alcock was rather upset at the speed at which their assigned officials had come to their aid, but when they appeared with another member of the legation, Mr. Macdonald who had been staying on the other side of the complex, it became apparent that there had been a full-on sword battle with the guards in the yard. Mr. Macdonald, who had been very conspicuous in his white pajamas and gown, had been saved when the guards had pulled him aside and draped him in a kimono to disguise him from the assailants.

The attack is said to have left sword cuts and shotgun holes in parts of the building that are said to still be there today (although the currently residing monk throws some doubts on whether the markings are actually from the attack).

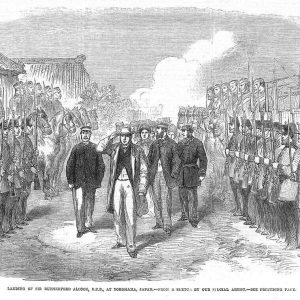

It was later discovered that the attack was made by samurai of the Mito clan, claiming to be a band of masterless warriors. According to the New York Times, which also reported the incident, three members of the party were killed outright, with a fourth mortally injured and taken prisoner. Three others who were closely pursued took refuge in a teahouse and committed ritual suicide (seppuku). One of the three was caught and saved before he died.

A declaration, signed by all of the members of the party, was discovered on each of them, thereby disassociating any blame towards the leader of the Mito clan. It read:

I, although a person of low standing, have not patience to stand by and see the sacred empire defiled by foreigners. On this occasion, I am resolved in my heart to undertake my master’s will. I alone cannot make the might of the country shine in foreign nations, but with a little faith and a little warrior spirit, if this action may in some way cause the foreigner to retire, and reassure both the minds/hearts of the Emperor and the Shogunate, I shall take it as the highest praise. I am determined to carry out this mission regardless of my own life. [Signed by the 14 members of the party.]

Following the incident, Alcock was sent home on extended leave. Lieutenant Colonel Edward St. John Neale was appointed the British chargé d’affaires in May 1862.

Just over a month later, in June, another attack was made on the legation which resulted in the deaths of two British Marines from the H.M.S. Renard. This prompted the legation to be temporarily moved to the British Garrison at Yamate, Yokohama.

Oliphant (who was a former secretary to Lord Elgin) had been severely wounded with deep cuts to his shoulder and arm that left him with permanent damage to his hand. He was sent on board a ship to recover. He later returned to Britain and resigned from the Diplomatic Service and went into politics.

Oliphant also authored books, was a writer for The Times newspaper, an agent for British Intelligence, as well as something of a mystic. Amid lots of furor, he later retired from politics to go help set up and live in communes in the United States. As you would expect of a rather colorful and diverse character like Oliphant, his story does not end there.

After suffering a severe wound to the head, Morrison also went back to Britain that autumn for a while to convalesce. When he finally returned to Nagasaki two years later, Japan was on the brink of civil war following the Satsuma and Choshu alliance. Suffering from continued health problems, and after receiving some serious threats on his life, Morrison decided to leave the service and Japan and returned to Britain.

-

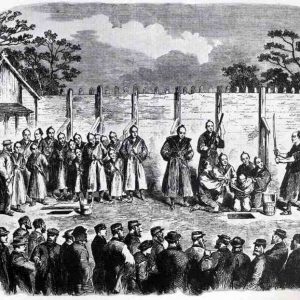

- 10. A samurai being executed for the attack on the sailors at Tozenji (London Illustrated News, 1865)

John Frederick Lowder remained in Japan for the rest of his life. He went on to become a vice consul at Osaka, and acting consul at Kanagawa. He resigned from the diplomatic service in 1872, after being called to the bar, and became a legal advisor to the Emperor, for which he was eventually awarded the Order of the Rising Sun 4th Class. He later worked as a barrister in Yokohama. He died aged 59 in 1902, and is buried in the Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery, Kanagawa prefecture.

The current British embassy in Tokyo is located at No.1 Ichiban-cho, Chiyoda ward, very close to the Imperial Palace. After moving to Yokohama in the wake of the attacks in 1861-1862, the legation was due to relocate to an official residence in Gotenyama, Shinagawa. However, before it was completed, the building was destroyed by Sonno Joi forces, led by Takasugi Shinsaku of Choshu province.

Sir Harry Parkes, who was appointed a British minister in 1865, decided to survey former daimyo-held residences that had been forfeited during the abolishment of the domain system. He acquired the land in Chiyoda in 1872, and the legation opened there in 1874.

Following Japan’s development and military victories over China and Russia, the legation was upgraded to an embassy. However, many of the original buildings were destroyed in the Great Earthquake of 1923. Later, following the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, the embassy was closed until the allied occupation in 1945, when it was first used as a base by the Royal Navy, until it officially reopened as an embassy in 1952.

Part 2 of this series will focus on the Namamugi Incident, also known as the (Charles) Richardson affair.

-

- 2. Tozenji Circa 1868 by Lieutenant James Henry Butt. National Maritime Museum Collection, Greenwich, London

-

- 3. Tozenji Circa 1868 by Lieutenant James Henry Butt. National Maritime Museum Collection, Greenwich, London. This drawing shows Tozenji’s original Sanmon (gate) that no longer exists.

We would like to extend a special thanks to Sengan-en and the Shoko Shuseikan Museum for their cooperation.

Author: Paul Martin

You may like

-

70 Years of the Self-Defense Forces: Present Challenges

-

Gamer's World | Inside 'Assassin's Creed Shadows' and the Controversial Reaction to its Samurai Hero

-

The Politics of Japan's New Banknotes: From Fukuzawa to Shibusawa

-

Australia and Japan, Parallel Histories From Textbooks to Truth Boxes

-

INTERVIEW | 'Hagakure': The Colossal Task of Translating a Samurai Guide for Modern Minds

-

INTERVIEW | Editor of New 'Hagakure' Translation on What the Bushido Guide Offers the Modern World

You must be logged in to post a comment Login